Young and pretty, Jerusha Layne (Jeri Howard’s grandmother) spent five years in Tinseltown, working as an extra and bit player in the movies, hoping for stardom. But she found love instead, marrying Ted Howard in 1942, after Pearl Harbor changed everything. But was there another reason Jerusha left town, involving an actor’s unsolved murder? And how does this decades-old crime connect with movie memorabilia and modern-day murders?

Young and pretty, Jerusha Layne (Jeri Howard’s grandmother) spent five years in Tinseltown, working as an extra and bit player in the movies, hoping for stardom. But she found love instead, marrying Ted Howard in 1942, after Pearl Harbor changed everything. But was there another reason Jerusha left town, involving an actor’s unsolved murder? And how does this decades-old crime connect with movie memorabilia and modern-day murders?

“Delightful… Jeri has to wonder if someone is willing to commit murder in the present-day over two golden era movie posters. In flashbacks, Dawson does a fine job bringing WWII-era Los Angeles to life.”

—Publishers Weekly

“The local background is fun, Jeri is a believable character and the story of old Hollywood is engrossing.”

—Roberta Alexander, Oakland Tribune

“Jeri remains at the top of her game in this marvelous story…”

—Poisoned Pen Book News

“… a masterful, compelling tale rippling from the golden age of Hollywood to today. Rich in period detail—and a classic movie lover’s dream—it deserves a starring role on every mystery-lover’s shelf.”

—Kelli Stanley, author of City of Dragons

“Jeri Howard fans will cheer at this latest entry to a beloved series. Dawson expertly weaves a twisty mystery stretching from Hollywood’s golden years to the present day and its mania for movie memorabilia. Highly recommended!”

—Ann Parker, author of the Silver Rush historical mystery series

Excerpt:

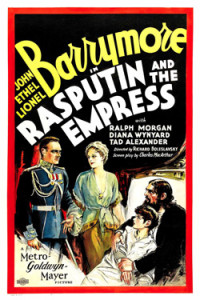

“Grandma said John Barrymore made a pass at her.” I nudged my friend Cassie and pointed at the framed poster from Rasputin and the Empress, displaying the famous profiles of John, Ethel, and Lionel in the 1932 film, the only movie the three Barrymores ever made together.

“Grandma said John Barrymore made a pass at her.” I nudged my friend Cassie and pointed at the framed poster from Rasputin and the Empress, displaying the famous profiles of John, Ethel, and Lionel in the 1932 film, the only movie the three Barrymores ever made together.

Cassie chuckled. “From what I’ve heard about John Barrymore, he made passes at anything in skirts.”

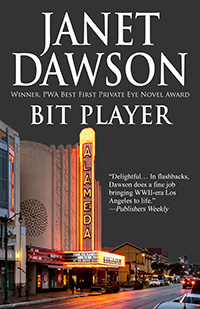

On this sunny Saturday afternoon, the last weekend in May, Cassie and I were in downtown Alameda, where we’d gone to a movie at the city’s newly restored Art Deco movie palace, glittering anew like the jewel it had been when it opened back in the 1930s.

Just opposite the theatre I stopped, lured by the display of old movie magazines and posters in the window of a shop that hadn’t been here the last time I’d been downtown, just a few weeks earlier. The sign above the door looked like a movie marquee, mirroring the real one across the street. The shop was called Matinee—Classic Hollywood Memorabilia.

I really like movie memorabilia, but I have to be picky and buy only what I can afford. I’m Jeri Howard, self-employed private investigator, with a slim profit margin, a mortgage payment to make, and not much room in my budget for frills.

“When did your grandmother encounter John Barrymore?” Cassie asked.

“On the set of Marie Antoinette. Barrymore was playing King Louis the Fifteenth.”

Grandma was thrilled to be an extra in the lavish costume drama, in production at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in the spring of 1938, especially because she was in a scene with her favorite actress, Norma Shearer, who starred as the doomed queen. The movie also featured handsome young Tyrone Power and a panoply of Hollywood names, including Barrymore.

My grandmother, Jerusha Layne, went to Hollywood in the fall of 1937. She was eighteen, just out of high school. Ever since she was old enough to stand on a box behind the counter, she’d worked in her family’s theater in Jackson, California, selling tickets and popcorn, enthralled by the movies spinning from the huge reels her father wrestled onto the projector upstairs in the booth. She wanted more from life than she could find in that small Gold Rush-era mining town. The new gold rush, for pretty young women like Jerusha, was to Hollywood. Visions of movie stardom beckoned, as ethereal as El Dorado’s glittering dust. Lightning could strike. She could climb the ladder to the top. After all, she sang, she danced, and she’d played the lead in several high school plays.

Except it didn’t work out that way. Pretty and talented as she was, Jerusha discovered lots of young women just like her, scrabbling at the bottom of that Hollywood ladder, trying to get their feet on the first rung. She worked in the movies, all right, first as an extra, a silent face in the crowd, walking down a sidewalk or sitting at a table at a restaurant, filling in the background while the cameras focused on the stars. Then she worked as a bit player, or day player, as they were sometimes called. Bit players were different from extras, because they had a few lines of dialogue, or they did bits, specific pieces of business. Jerusha played telephone operators, hat check girls, waitresses. She was the shop clerk, chatting while she waited on the star, or the neighbor who witnessed the gangland shooting and gave a statement to the cops. She got jobs through agents, but often bit players weren’t under contract like actors who worked steadily in larger roles. As she sat in the background, Jerusha dreamed of the day when the parts would get bigger, when someone at a studio would notice her and offer her a contract.

It didn’t happen. But Jerusha stuck it out for nearly five years, working primarily at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Then she left Hollywood, realizing her future wasn’t written in lights on a movie palace marquee. Besides, she’d met a young man named Ted Howard. They married in the spring of 1942, like so many young couples in those war years, full of hopes and fears for the future. Later that year, Ted Howard, United States Navy, left to fight battles in the remote islands of the Pacific. But he came back, and my father, Timothy, was their firstborn. Grandma never had any regrets, but she certainly had some great Hollywood stories to tell her grandchildren. And I—the granddaughter named after her—relished every tale.

“I’ve always wanted something from one of Grandma’s movies,” I told Cassie. “A one-sheet, an insert, a title or lobby card—that would be great. This is a lobby card.” I pulled one from a nearby bin. Encased in a clear plastic sleeve, the eleven-by-fourteen-inch card displayed a color photo of Marilyn Monroe, Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon in the Billy Wilder masterpiece, Some Like It Hot.

“Lobby cards showed colored photos of scenes from the movie,” I explained, “even if the film itself was shot in black and white, like this one. The cards usually came in sets of eight. They were displayed in theater lobbies. You don’t see lobby cards for movies made after the early sixties. I guess they stopped making them. Sometimes there was a ninth card in the set, a title card. Instead of photographs, title cards showed the title, names of the cast, and an image, usually the same as on the one sheet.”

I gestured at the posters ranked along the walls—William Powell and Irene Dunne in Life with Father, Robert Mitchum and Deborah Kerr in Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison, Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. “These are one-sheets. A one-sheet is a full-size movie poster, twenty-seven inches wide and forty-inches high. There’s a larger size poster called a three-sheet, which is forty-one inches wide by eighty-one inches. Got to have a lot of wall space for one of those. But an insert is a good size for display, thirty-six inches high, but narrower, about fourteen inches.”

I hadn’t seen anyone behind the counter when Cassie and I had walked into the shop, though a tinkling bell above the door had announced our entry. But I’d been focused on the shop’s wares. Now I tuned in my surroundings.

A man perched on a stool, partly hidden by the cash register and the old issue of Lifemagazine he’d been reading. He cleared his throat. His voice sounded rusty and disused. “I couldn’t help overhearing,” he said, setting aside the magazine. “Your grandmother worked in Hollywood?”

“She was a bit player, from nineteen thirty-seven to nineteen forty-two.”

“Ah, I remember,” he said. “Those were golden years. What was your grandmother’s name?” he asked.

“Jerusha Layne.”

His thin lips curved into the ghost of a smile. It didn’t fit his face, making it look instead like one of those masks. Comedy or tragedy, I couldn’t tell which. “Jerusha Layne,” he repeated, tasting the vowels and consonants. “An unusual name, very pretty. I imagine she was pretty. They all were. Where did she work? At what studios?”

“She worked mostly at Metro, though she did a few films at Warner, RKO, and Columbia. She was in the last six films Norma Shearer made before she retired. Well, before they both retired, Norma and Grandma. Do you have lobby or title cards from any of those Shearer movies?” I asked.

“Let me check our inventory. I believe we do have some stock from The Women.” He stopped at one of the bins. His age-mottled hands quickly flipped through the unframed, plastic-covered cards. He pulled out two title cards and handed them to me.

“Voilà,” he said. “The Women, released September nineteen thirty-nine. And We Were Dancing, released in nineteen forty-two. Both of these cards are vintage. Lovely, aren’t they?” The man looked at me as though he knew he had a live one on the hook. “And in great condition.”

Not that I needed much convincing. “I’ll take both of them.”

The proprietor moved slowly now as he walked back behind the counter, as though he’d expended his day’s ration of energy. He rang up the sale, ran my credit card through the machine, slipped the title cards into a bag and handed them to me. Then he placed his right index finger next to his mouth and tilted his head to one side. It was a little too studied, a parody of a natural movement. The broad gesture, I thought, of an actor from the silent era, miming a man who was searching his memory.

“Jerusha Layne,” he said, with a dramatic wave of his hand. “I remember now. She was involved in that business with Ralph Tarrant, in ’forty-two.”

“Who was Ralph Tarrant?”

“A British actor who came to Hollywood in nineteen thirty-six. He was in Lloyd’s of London, with Tyrone Power. Had a marvelous voice. Quite handsome as well. I don’t know all the details,” he said. “Just what I read in the papers and heard on the grapevine. Probably nothing more than gossip. Hollywood simply thrives on gossip.” A malicious smile teased the corner of the old man’s mouth.

“The story was that Jerusha Layne and Ralph Tarrant were, shall we say, an item. Then they broke up. Not a friendly parting of the ways. So the police were rather interested in her whereabouts the night Tarrant was murdered. Rumors about who did it were flying all over town.” He fluttered his hands, miming the wings of a bird. “It was quite the Hollywood mystery, you see. Still is. The murder was never solved.”