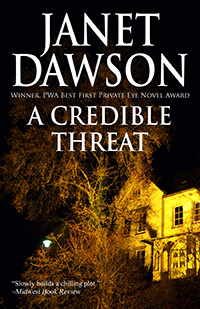

A Credible Threat is a term from California’s anti-stalking law. And it looks like the University of California students who share a big old house in Berkeley are under siege. Vandalism, threatening phone calls, then frightening violence. Could murder be next? Or has it already happened?

A Credible Threat is a term from California’s anti-stalking law. And it looks like the University of California students who share a big old house in Berkeley are under siege. Vandalism, threatening phone calls, then frightening violence. Could murder be next? Or has it already happened?

“The last third of the book is a classic deduction, investigation, chase sequence. In Dawson’s capable hands, the characters are believable and the story moves forward in a lively fashion.”

—The Contra Costa (CA) Times

Excerpt:

“What the hell happened to the lemon tree?”

The woman stood in the uncarpeted foyer of the house on Garber Street, hands on her hips and a scowl on her face.

I glanced at Vicki Vernon, pacing like a restless tiger cat, back and forth across the worn red and black Turkish kelim. Now she stopped, widening those golden brown eyes that reminded me of her father.

“Sasha,” Vicki said, addressing the newcomer.

Sasha, still scowling, moved toward us. Tall and dark, with short curly black hair that set off the big gold hoops in her earlobes, she wore loose-fitting blue jeans, a purple turtleneck visible over the collar of her denim jacket. She carried a red nylon backpack slung over her left shoulder. Behind her I saw a little boy, about six, wearing baggy brown cords and a yellow sweater, a bright orange child-sized pack on his back. He stared at me with wide brown eyes, one hand cradling the ripped stem and torn petals of a pink tulip.

Sasha ignored me and fired words at Vicki. “What the hell happened to the lemon tree? And the rest of those plants? There’s dirt and leaves and flowers all over the porch and the sidewalk.”

“Vandalism,” I said. “We think.”

Both of them turned to look at me. I’d been sitting at one end of the high-backed persimmon-colored sofa that faced the front windows, its bright upholstery clashing with the dark red of the carpet. Now I stood up. Vicki made the introductions.

“Jeri, this is Sasha Nichols, our landlady. Sasha, this is my… this is Jeri Howard. I told you about her.”

“The private investigator who used to be married to your father.” Sasha slipped the backpack from her shoulder and set it down next to the sofa. “Since when do you call a private eye to report vandalism?”

“Vicki tells me it may not be as simple as that.”

Sasha frowned. The fading light of the March afternoon cast her strong features in relief. “Maybe not.” She turned and looked at the child behind her, then patted the youngster on his shoulder. “You can play in the back yard until dinner, Martin. Then we have to do our homework.”

The little boy, still holding the ruined tulip, opened the door on the opposite side of the hallway. I knew from what Vicki had told me that it led to her landlady’s quarters, occupying nearly half the house’s lower floor. The room where we were now had been the formal dining room. It was now the living room which, along with the large kitchen visible through an open doorway at the rear, was shared by all the residents.

Somehow, when Vicki described her living arrangements, I’d assumed her landlady was older. A professor’s widow, perhaps, forced by financial circumstances to turn her home into a rooming house. However, Sasha Nichols was in her early thirties at most.

The house was a rambling two-story structure, a brown shingle, one of many similar houses in Berkeley’s Elmwood District. Many of these houses had been built in the early part of this century and were prized for their comfort and space. If it were for sale, the down payment on this house would be more than I made in a year. I could only guess at the yearly property taxes and the cost of heat, light, and water.

I was sure my theory about the landlady’s tight money was correct. The place was in need of maintenance. Outside I’d noticed the usual things a homeowner has to deal with on a regular basis—the roof, the rain gutters, the exterior shingles that covered the sides of the house. All of these showed signs of neglect, and I’d seen a cracked windowpane downstairs, in Sasha’s quarters. Inside there were hairline cracks on the high ceiling. It looked like the walls needed repainting. Patches of wear on the Turkish carpet and the sofa and chairs grouped around the coffee table gave evidence of years of use.

“Anyone going to tell me what happened?” Sasha lowered her voice, already an alto purr, and looked sharply at Vicki.

“Emily and I found the plants when we got home from class,” Vicki said. “Emily was really upset.”

As if on cue, footsteps sounded behind us as another person crossed the threshold from kitchen to living room. Emily Austen, one of Vicki’s housemates, carried a round brass tray with three mugs of coffee, a sugar bowl, and a small pitcher. She stopped when she saw her landlady. “Sasha, I didn’t hear you come in. I’ll get another mug.”

She set the tray on the coffee table and quickly headed back to the kitchen, returning a moment later with a fourth mug. She gave it to Sasha, then sat down on the sofa, and picked up her coffee. Vicki perched next to her.

I resumed my seat and reached for one of the steaming mugs. I took a sip and felt a caffeine jolt surge through me as I examined Emily. If Vicki was a vigorous tiger cat, always in motion, Emily was a quiet brown wren, one who never had much to say. Her dark brown hair fell in waves past her shoulders, caught on either side of her temples with matching blue barrettes. She didn’t look upset now. I saw a touch of wariness in the blue eyes that looked out from her pale face. Was she wary of me, or of strangers in general? She seemed very much in Vicki’s shadow, but something made me think that first impression was erroneous.

Mug in hand, Sasha arrayed herself tiredly on the cushions of a wing-back chair and put her feet up on the coffee table.

“It’s a lovely house,” I said. “How long have you lived here?”

“Most of my life.” Sasha sipped her coffee. Now that she was closer to me I could see lines of fatigue in her dark face. “The house belonged to my parents. My father was professor at the university. I’m what they call a faculty brat.” She looked expectantly at her two tenants. “Let’s talk about the plants.”

It was the sight of the lemon tree that had upset Emily, according to Vicki. The tree’s fate would bother anyone who’d seen the deceased. It pricked at my mind too. But I couldn’t recall why. Citrus trees were common enough in the Northern California landscape. In fact, there was one in the courtyard of my apartment complex, near my front porch. I pictured the little tree with its dark waxy green leaves. We’d had an early spring following a cold rainy winter and the tree was now loaded with fragrant yellow-white blossoms, harbingers of the hard fruit that would soon appear and ripen from green to yellow.

But the lemon tree Vicki and her housemates had planted would never bear fruit. I’d seen what remained of it when I arrived, fifteen minutes before Sasha. The little tree, about three feet tall, and the other foliage, had been planted in several large clay pots that had then been arranged on both sides of the steps leading up to the porch. When Vicki and Emily returned from classes at U. C. Berkeley earlier this afternoon, they found the plants destroyed, their carcasses littering the sidewalk and porch, a testament of desecration that cast a pall over what had been a pleasantly mild and sunny Friday in March.

I’d had to sidestep potting soil, broken bits of clay and the smashed remains on my way up the steps. Two azaleas and two hydrangeas had been ripped from their containers and shredded into debris. The pots were smashed against the porch railing. Tulips and daffodils, both bulbs and blooms, had been stomped to a messy pulp under someone’s feet.

Pulled from its pot, the lemon tree had been decapitated, its trunk chopped with an ax or a hedge cutter. The dark green top, with its tiny buds, was arranged on the wooden porch, the chopped off end pointing toward the front door. The lower half sat alone in the middle of the front porch, resting lopsidedly on roots that bled potting soil.

At first, compared to the other plants, the lemon tree looked relatively unscathed. But on further examination, I decided that it had been singled out. Tossed, like a gauntlet.

The destruction could have been committed by some random vandal who’d seen the plants as an easy target. Berkeley certainly had its share of crime, no more immune to the underbelly of modern life than its neighbor, Oakland. But I didn’t think so. The mess littering the front of the house looked more like a calling card than an impulse.

Who was leaving the message? And why?